How Mellanox set the stage for NVIDIA’s AI dominance and signaled the Storage Supercycle

Deep dive into MLNX+NVIDIA partnership, GPUDirect RDMA, GPUDirect Storage, Bluefield DPU, Spectrum-X, and what could be coming next

If I had to summarize the NVIDIA + Mellanox relationship in a single sentence, it would be this: Every time GPUs got faster, the network became the bottleneck — and NVIDIA and Mellanox kept removing that bottleneck layer by layer.

This article traces the pivotal innovations that emerged from this partnership and how it put NVIDIA in the dominant position it is today. We’ll dissect how Jensen played his hand in five phases, each one pushing the GPU further out of its role as a graphics “sidekick”, to becoming the heart of the modern AI data center.

2009: GPUDirect Shared Memory — Breaking the ice between the GPU and the NIC.

2013: GPUDirect RDMA — NICs and GPUs learn to talk directly, accelerating the GPU-to-GPU path.

2019: GPUDirect Storage — The storage bottleneck is removed, accelerating the path from SSD to GPU.

2022–Present: Spectrum-X & BlueField. Building AI factories, and taking over the data center to challenge Broadcom.

Retrospective analysis and the Future — What’s next for the GPU-centric architecture?

By the end, you’ll see how the signal for companies like SNDK 0.00%↑ , WD 0.00%↑ were visible much earlier than most of us realized — it was in front of us all along.

The story goes like this…

2009-10: Tianhe-1A and China’s Emergence in Supercomputing

In 2009, during the Tesla and Fermi era of NVIDIA GPUs, there was a surge of interest from the scientific and high-performance computing (HPC) communities in using GPUs to accelerate computation.

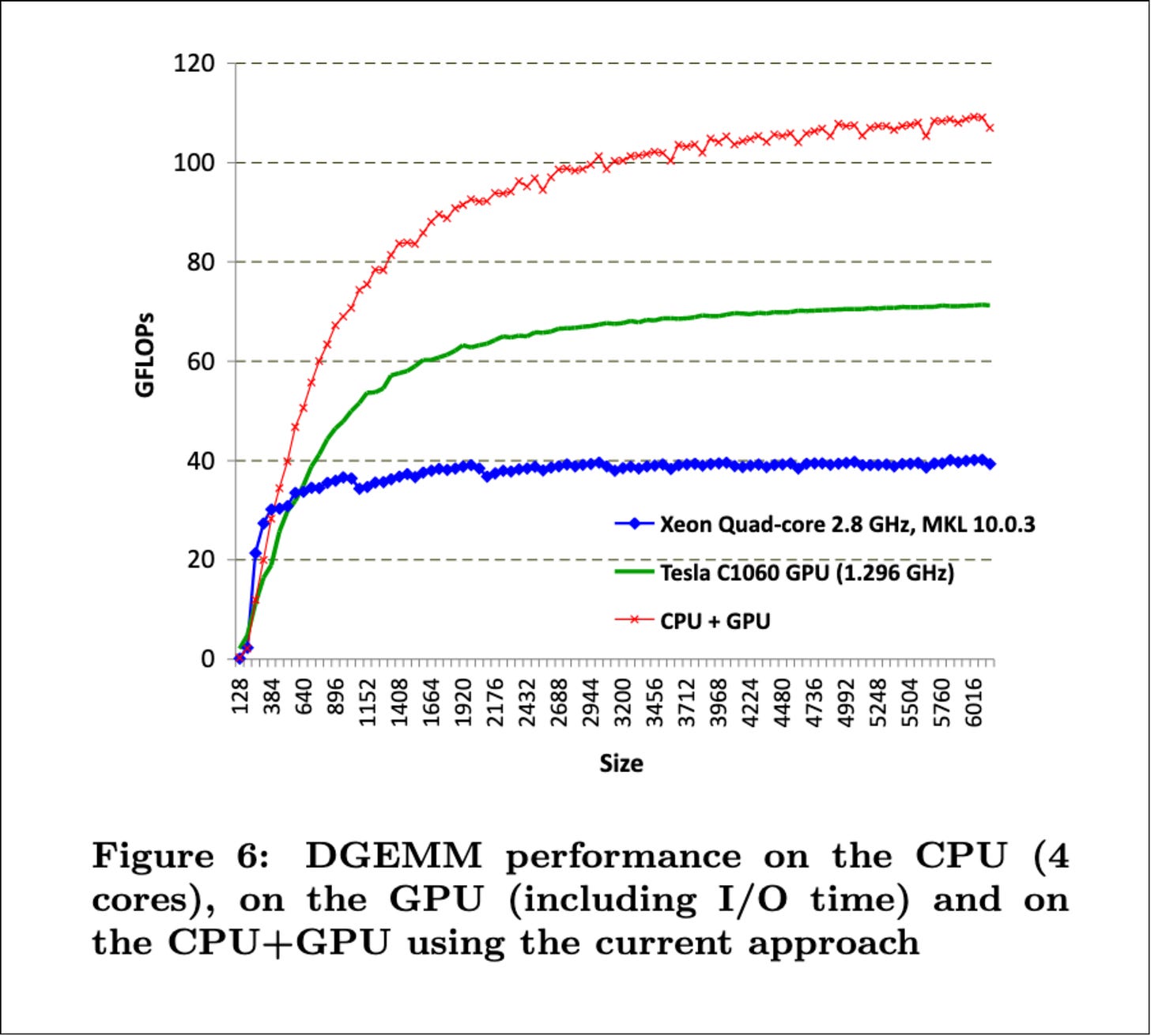

This interest wasn’t speculative. Real work was already showing that GPUs could fundamentally reshape the computing landscape. For instance, NVIDIA demonstrated that LINPACK, the benchmark used to rank the world’s fastest supercomputers, could be accelerated with GPUs.

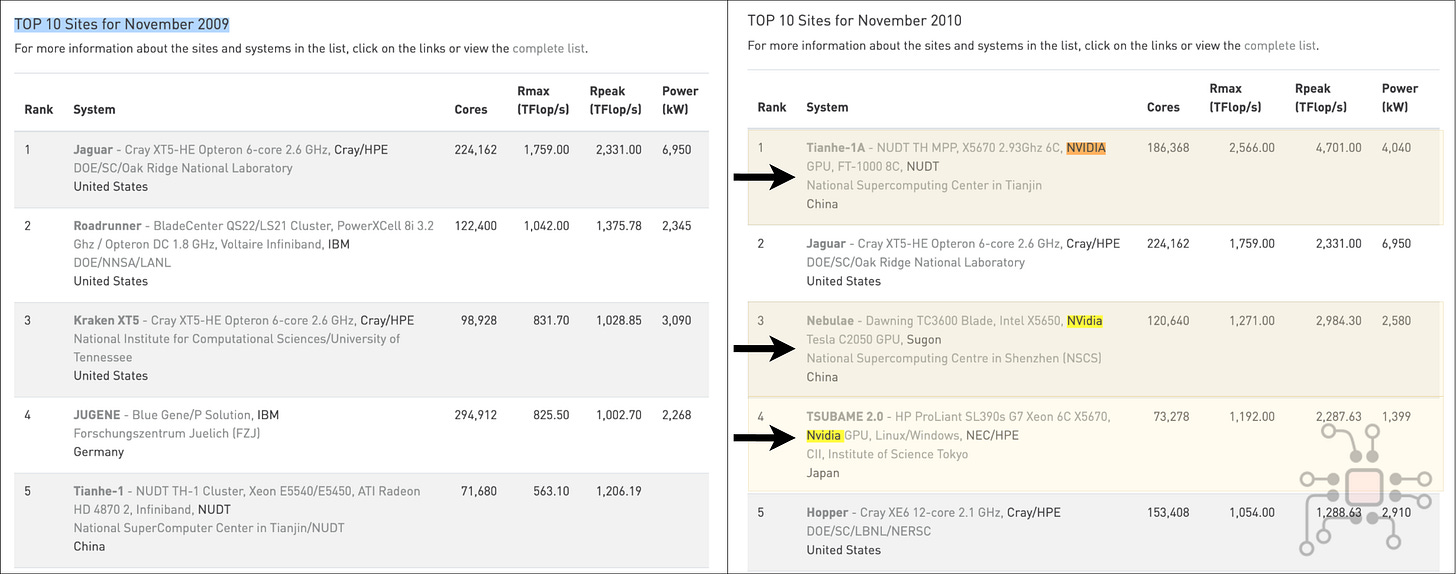

At the same time, China’s ambition to enter the supercomputing arena had become obvious. System by system, they climbed the TOP500 rankings. Then, in November 2010, they did it. Tianhe-1A, installed at the National Supercomputing Center in Tianjin, surpassed the American Cray XT5 supercomputer, installed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory to claim the #1 spot. It marked the end of a decade-long period of U.S. dominance.

What’s remarkable isn’t just that China took the top position — it’s how quickly the underlying architecture shifted. If you compare the Top 5 supercomputers from November 2009 to November 2010, we see that in the span of a single year, three of the top five supercomputers are now GPU-accelerated, using NVIDIA GPUs.

The promises that GPUs were living up to in this era had nothing to do with AlexNet, or deep learning, or transformers. This was pure high-performance computing. Which makes me think that Jensen’s conviction in GPUs as a foundational computing primitive long pre-dated AI as we know it today.

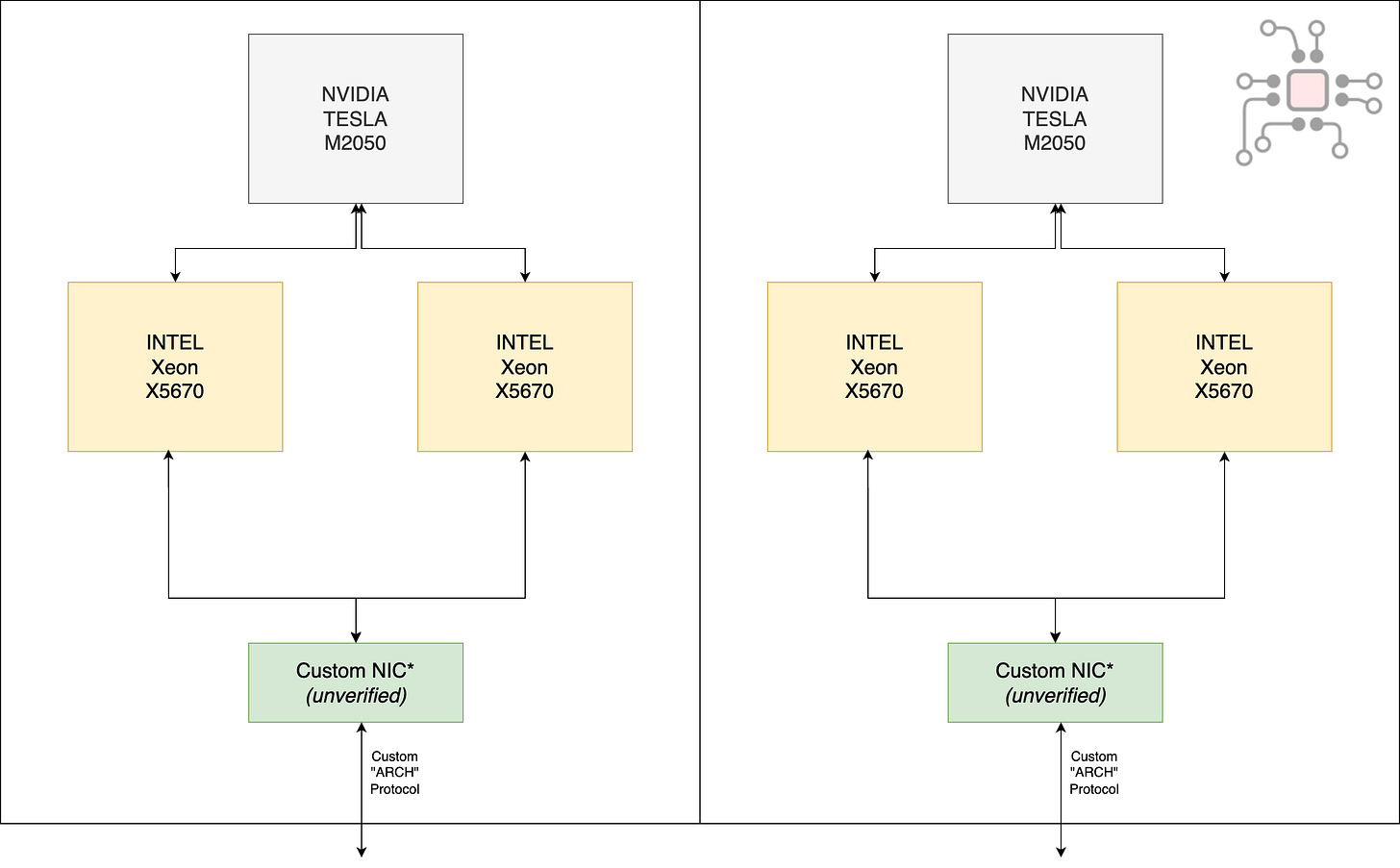

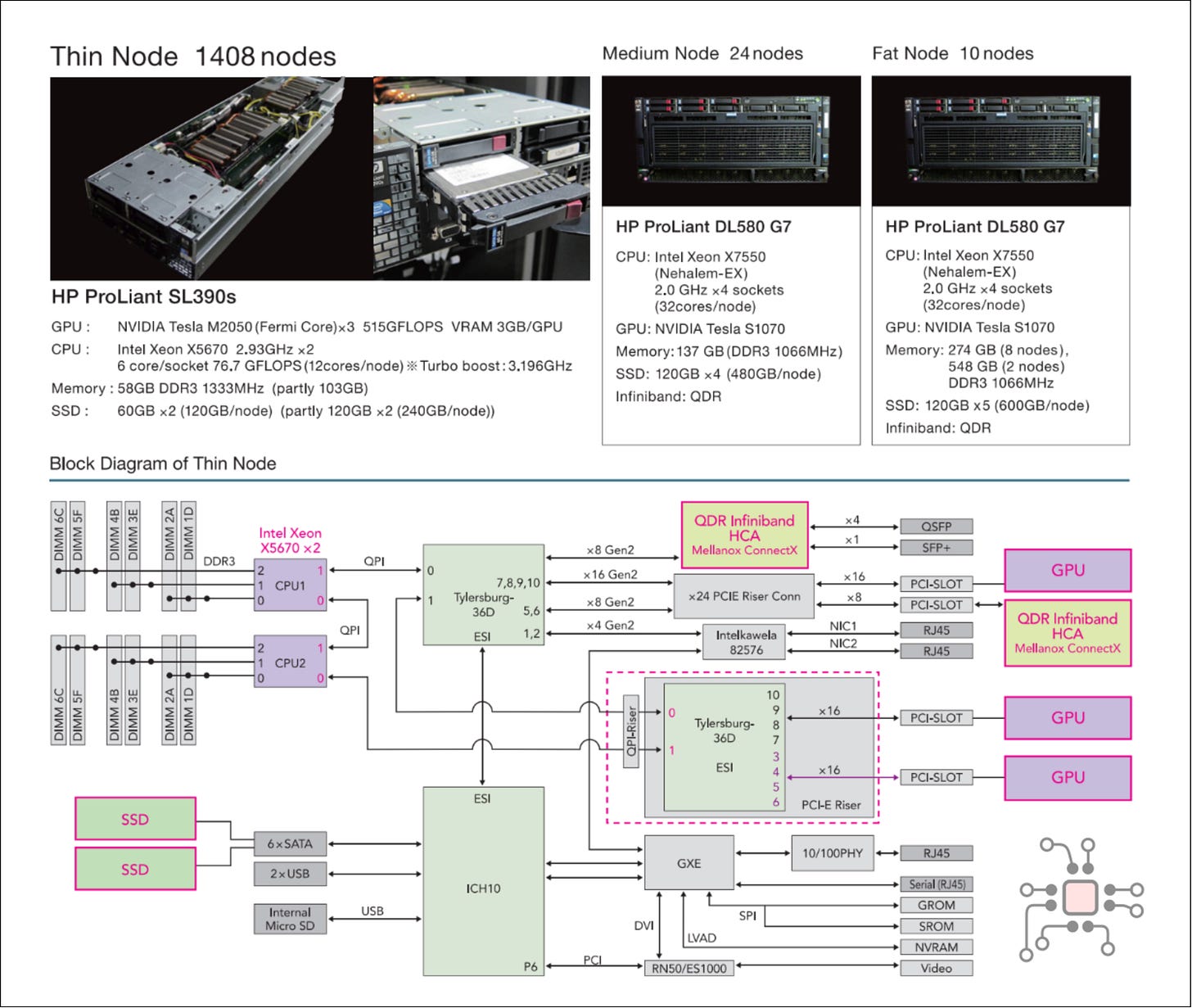

It’s not hard to draw architectural parallels between Tianhe-1A’s compute trays and something like a modern GB200. The machine was composed of:

14,336 Xeon processors and 7,168 NVIDIA GPUs. Arranged in 3,548 compute trays, each containing two nodes.

Each node had 2× Intel Xeon X5670 6-core CPUs and 1× NVIDIA Tesla M2050 GPU.

The interconnect was proprietary, which delivered roughly 2× InfiniBand bandwidth at the time.

While Tianhe-1A and several other signs showed that GPUs were the future of high-performance computing, there was a fundamental problem.

In order for large compute clusters to work together cohesively as one unit, they have to communicate through high-speed links. But, GPUs were stuck behind CPUs. Every movement of data had to be orchestrated by the host CPU. GPUs couldn’t talk to the network directly. They couldn’t talk to storage directly. They were fast, but fenced in.

That bottleneck set the stage for what came next.

In 2009, NVIDIA and Mellanox formed a partnership to address exactly this problem — how to liberate GPUs from the CPU-centric data path and make them first-class citizens in the data center.

2010: GPUDirect “Shared Memory” — Fermi + Connect-X2

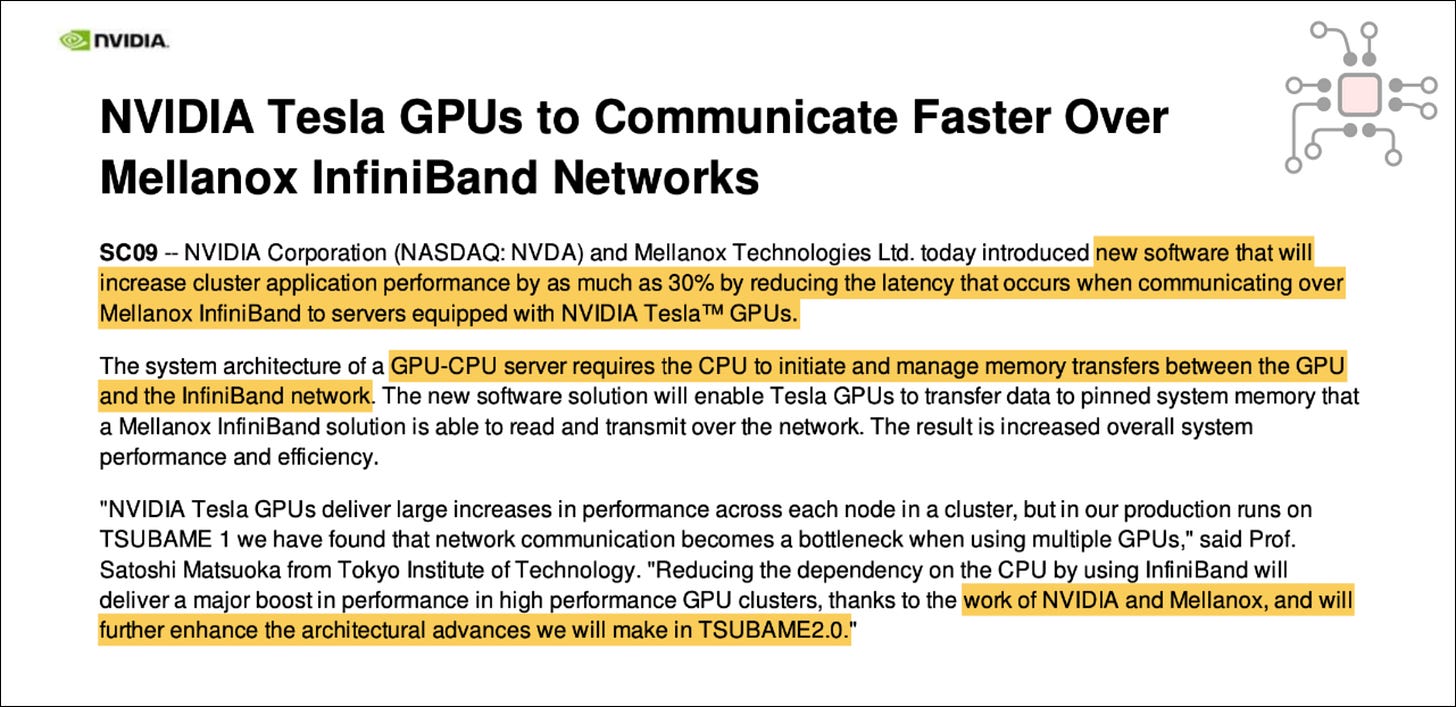

At SC09 (Supercomputing 2009), NVIDIA and Mellanox formally announced their partnership.

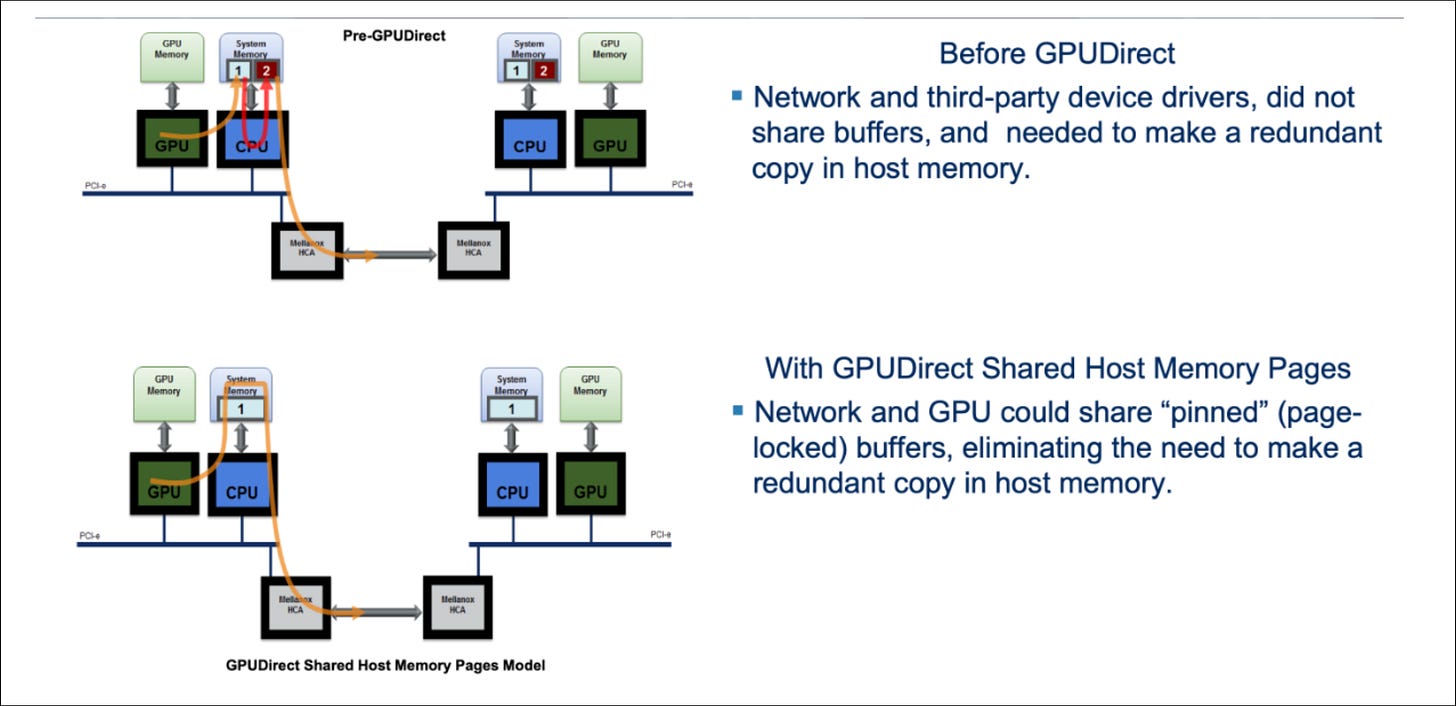

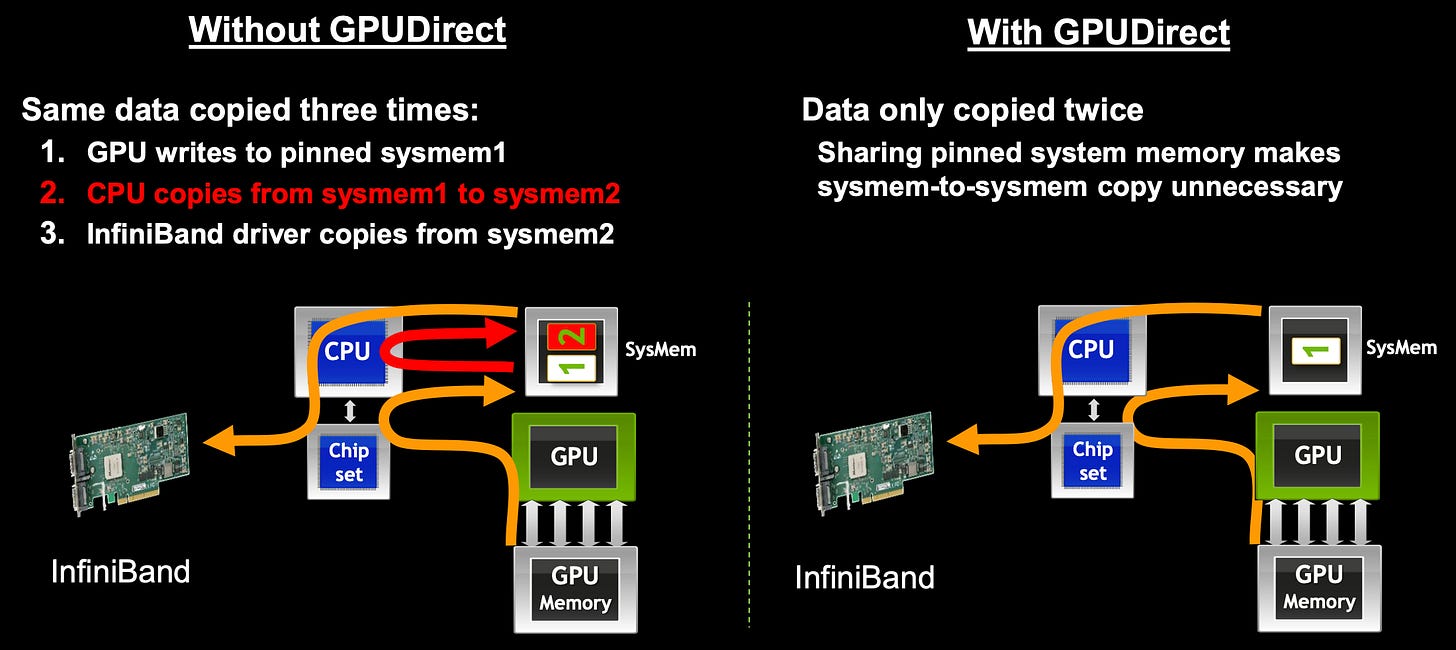

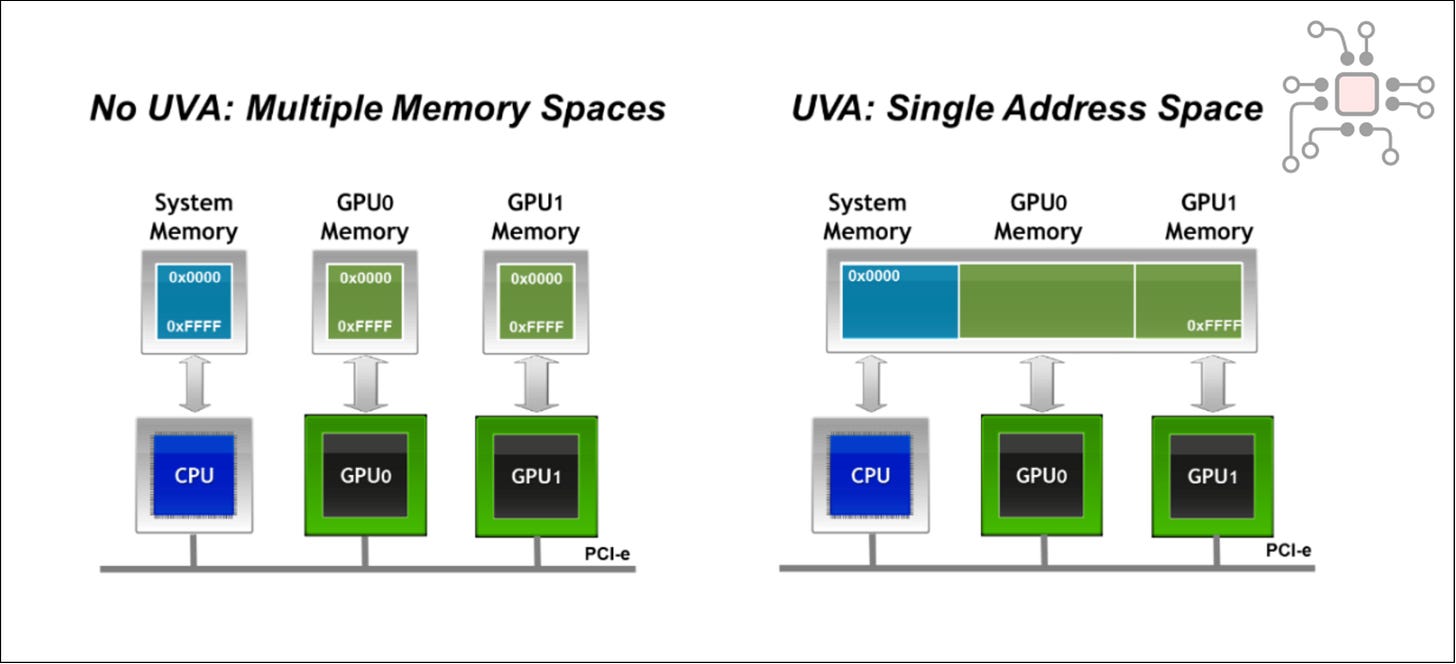

At the time, a typical GPU-accelerated server looked like this: a CPU running Linux acted as the master, with a GPU and an InfiniBand NIC attached to it over PCIe. During PCIe enumeration, the GPU and the Mellanox card were assigned separate address regions in CPU’s memory (host memory). As a result, the CPU was responsible for initiating and orchestrating all data movement between the GPU and the InfiniBand network.

This led to an especially wasteful stage in the data path called buffer copy. The GPU puts data in System RAM (Buffer A). The CPU reads Buffer A and copies it to Buffer B (which the Network card can see). Their first goal with this partnership was quite simple — eliminate this buffer copy step.

Sounds deceptively simple, but in order to make this happen there were 3 changes necessary:

Linux kernel updates to allow NVIDIA and Mellanox drivers to share host memory. This made it possible for the InfiniBand NIC to directly access buffers allocated by the CUDA library, eliminating the need for buffer copies.

Driver updates on both sides. The NVIDIA and Mellanox card drivers had to shake hands and agree to use Buffer A for everything.The Mellanox driver registered callbacks that allowed the GPU to notify any changes performed during run time in the shared buffers.

This simple update accelerated GPU communications over Infiniband by 30%. More importantly, it broke the ice between the GPU and the NIC. This was the first step toward direct, coordinated data movement.

2013: GPUDirect RDMA — Kepler, Connect-X3, accelerating GPU-GPU path

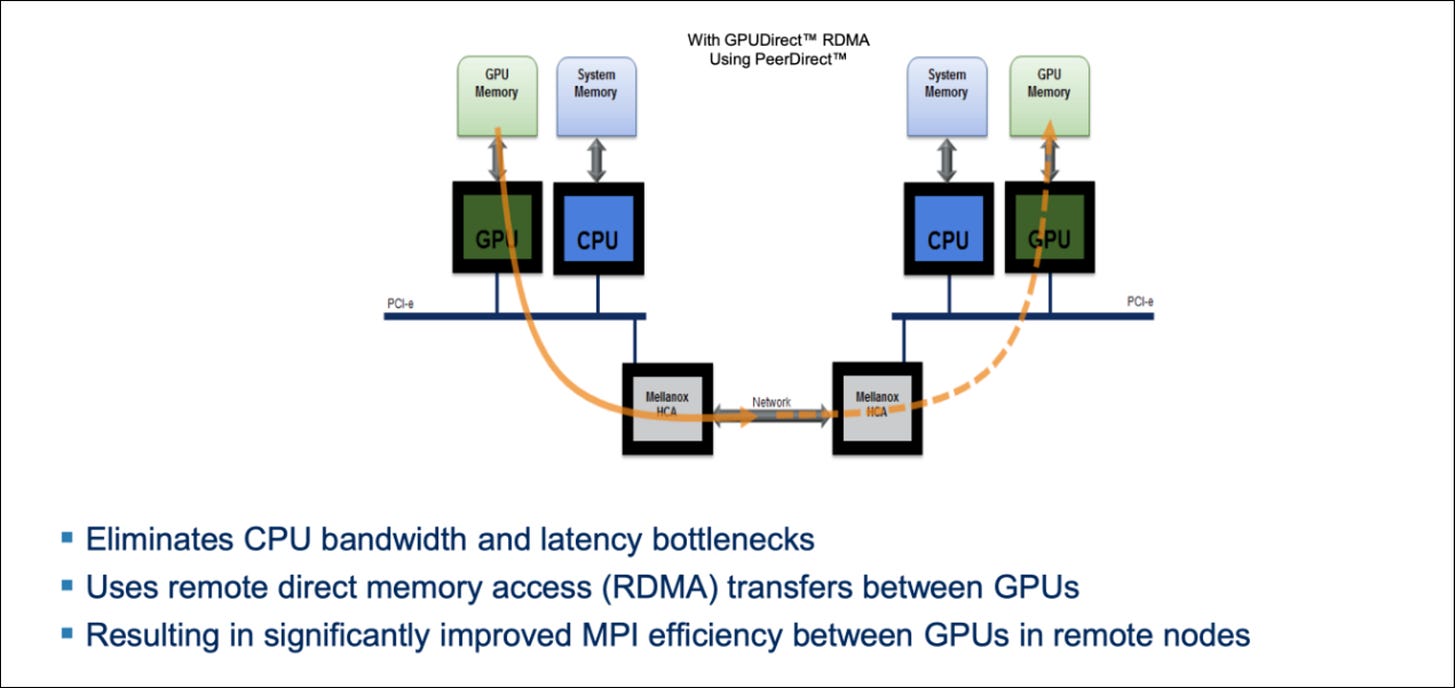

Even with the 2010 GPUDirect improvements, data still had to detour through the CPU’s system memory. That extra hop added latency and capped bandwidth at the speed of the host memory bus.

Which naturally raised the question — why can’t the NIC just read directly from the GPU’s memory?

That question is exactly what GPUDirect RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) answered and it became possible with the Kepler-class GPUs (NVIDIA Tesla K40).

Why this wasn’t possible before Kepler

On older GPUs (Fermi and earlier), the interface between PCIe and GPU VRAM was fundamentally constrained. Although a GPU might have had 6 GB of VRAM, only a relatively small aperture (typically ~256 MB, exposed via BAR1) was addressable from the PCIe bus at any given time.

To access data outside that window, the NVIDIA driver (running on the CPU) had to reprogram the BAR1 mapping to point to a different region of VRAM. The GPU would slide the window, and only then could the CPU read the data. This remapping was entirely CPU and driver-controlled, and devices like a Network Card are not smart enough to issue these “Move Window” commands. It just sends a “Read” request to a physical address. Without a stable, fully mapped view of GPU memory, direct access was impossible.

What changed with Kepler

Kepler fundamentally changed this model.

With Kepler, NVIDIA exposed the entire GPU VRAM address space directly to the PCIe bus. This meant that a NIC could now access any location in GPU memory at any time without CPU involvement and without remapping windows.

For the first time, the network could treat GPU memory as a first-class RDMA target.

The software stack catches up

On the software side, NVIDIA introduced GPUDirect RDMA support in CUDA 4.0, while Mellanox updated their MLNX_OFED drivers (i.e., the infiniband drivers) to enable true peer-to-peer RDMA paths between GPU memory and Mellanox adapters such as the ConnectX-3. Together, this enabled a direct data path between the GPU and the NIC.

GPU VRAM ⇄ Mellanox NIC ⇄ Network

How programmers actually used it: CUDA-Aware MPI

Next, it’s important to understand how exactly programmers used this feature. The real unsung heroes are the developers/maintainers of MPI (Message Passing Interface), which is a standard library used in HPC. It’s how partial results of computations are exchanged between nodes of a cluster, when trying to solve one giant physics problem.

Before GPUDirect RDMA, the MPI code had to copy over data from the GPU to the CPU’s memory using cudaMemCpy(*gpu_mem_ptr, *host_mem_ptr), and then sent the data to the peer using MPI_Send(*host_mem_ptr).

With GPUDirect RDMA, the MPI libraries were updated so that you could invoke MPI_Send(*gpu_mem_ptr) directly. Underneath the hood, this would tell the NIC to go read the GPU memory directly. The cudaMemCpy(gpu2host) step was eliminated entirely.

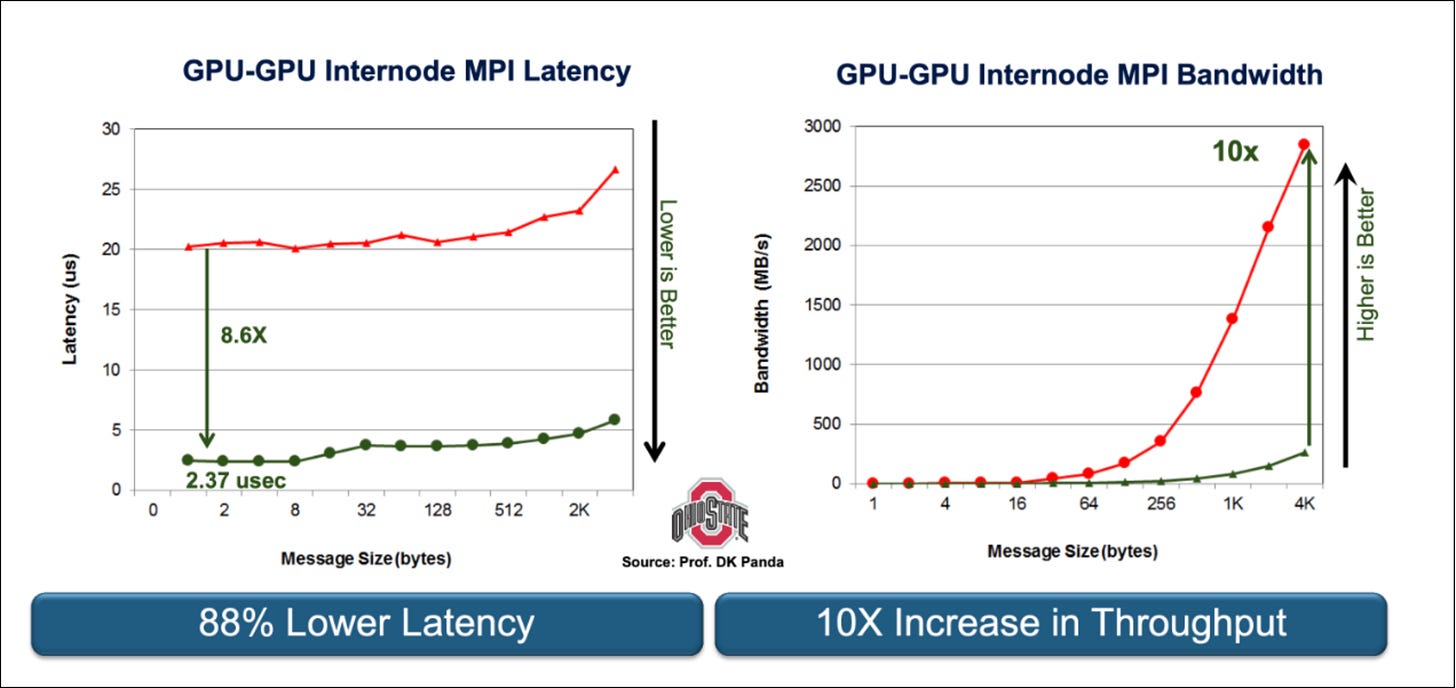

Once again, the change to MPI looks deceptively simple but the implications and work involved to enable it were profound. In 2013, the MPI core developers presented this update publicly, showing concrete improvements in both latency and throughput enabled by GPUDirect RDMA. It’s well worth watching that presentation to understand just how significant the shift was.

NVIDIA also published a detailed developer blog walking through how to use CUDA-aware MPI in practice, and benchmarking CUDA-Aware MPI.

2019: GPUDirect Storage — Accelerating GPU to SSD data path

By the end of the 2010s, you could see NVIDIA’s attention shifting to storage.